***

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button’s world looks painted—like a painting, it’s a selective recreation of reality, history designed to the frame, with light traced in neat, neoclassical lines through shadows. Magnificent Obsession’s world is just as painterly, directed by ex-painter Douglas Sirk, if more abstract: colors flare from black, faces are grainy, more light-effects, and Sirk patterns his characters against stripes, for texture, almost like Rauschenberg and Johns about the same time:

A melodrama set in front of a bunch of abstract expressionist installations—maybe—but Magnificent Obsession doesn’t look painted. It looks staged. Button is neatly composed of radios and top hats and nannies, its direction just a matter of storyboarding and fitting the scene to the frame. People are just objects to be placed in the pattern. But the compositions in Magnificent Obsession can change, dynamically, as the camera pans, doors open into background rooms, and the camera can come across a character on the side.

Magnificent Obsession doesn’t tailor its elements to the frame, even if every shot feels self-contained, but tailors its elements to the characters. Curtains and windows open up around them, while tables and furniture are directed toward them. Sirk makes them the center of the world—

—and as it turns out, they are, everything and everyone acting for their sake, in a film in which the music emotes their volcanic feelings for them, streaks of color alight from black as passions burst—

—and the most shadowy scenes of all seem imagined by the blind heroine as she visualizes the scene around her out of dark. The film contains three God figures, but that’s typical Sirk: girls can kill their parents by merely thinking it, with the invocation of a death dance in Written on the Wind or Imitation of Life, just as Helen Phillips (Jane Wyman, playing 20 years over her age) can summon her one true love into her room at a moment of despair, just by thinking about it, in Magnificent Obsession.

***

The usual question of whether or not Sirk is sincere—on the one hand, his films made millions cry; on the other, he deliberately uses formal distancing devices like windowpanes and curtains that nobody but Sirk’s title card illustrators and Sirk himself noticed before Fassbinder—comes up again in good service essays by Geoffrey O’Brien and Thomas Doherty on the Criterion disc of Obsession. Both defend his sincerity, which is sort of like defending Chaplin's sincerity. As Chaplin and Sirk's heroes are heroic idiots and layabouts, there are more sincere Chaplins and Sirks (City Lights, There’s Always Tomorrow) while there are more ironic Chaplins and Sirks (Monsieur Verdoux, and Written on the Wind, in which operatic music can grate against a prosaic scene on-screen). But wondering whether Sirk’s honest or sarcastic is like wondering whether men have hearts or minds, instead of wondering why they’re always opposed. Sirk uses both to opposite advantage. Shakespeare was his own conscious point of reference; Shakespeare had to try to find the art and universality and ordinariness in stories of murders, ghosts, incest, and other astonishing tales the public wanted to see precisely for their extraordinariness. Shakespeare responded by making his heroes self-conscious of the ludicrousness and vanity of the parts they play—in effect, letting his characters mock his stupid stories for him—and so the plays were great successes: the fact that Shakespeare characters know what they do, but do it anyway, only adds to the suspense and drama as they ponder their fate.

Sirk displaces both the grand emotions and the self-consciousness of their absurdity from his characters, innocent playboys and inchoate schoolmoms with untapped sex drives, played by solid actors like Wyman and Rock Hudson telegraphing their moods like Tex Avery wolves or Droopies, to the mise-en-scene. It’s as simple as what’s always said about Sirk, that he punches up the ludicrousness of his scripts with bright colors and boy choirs and emotional cues to heart attacks. There are all sorts of visual obstacles, from the doorways and bed frames and window panes and curtains, but they're used as much for visual irony as for restrictive structures the apoplectic characters can step beyond into the full light of revelation.

What irony there is springs from the same source as the sublime effect, from the idea that these two lovers’ love is the only thing in the world that matters (nearly every shot reflects it, and it’s certainly all that matters to the lovers)—

—that the rest of the world never intrudes.

Magnificent Obsession’s set is a set, and a closed one, for all its camera-pans and doors swinging open, and just as waves burst as lovers kiss in Vertigo, Magnificent Obsession, like Shakespeare, like Hitchcock, plays with the awesome idea most people probably play with, that the world outside is a theater starring themselves, reflecting themselves, and that their ludicrous emotions have some even more ludicrous correlation in the bright lights and dark shadows all around them. Sirk shows up their feelings as pure theatrics, with spotlights and sleepwalkers’ epiphanies, but this is also how he shows the feelings. They are ludicrous: for Sirk feelings are ludicrous, and if they didn’t bypass logic, people would probably be smart enough not to feel them. Sirk’s no more or less a Romantic Ironist than Hitchcock, Mann, Shelley, or Euripides: he knows the stupidity of saying men are worthy of mountains and Gods, and the greater stupidity in not saying it.

***

Back—to a film with three Gods, and a director whose characters can invoke deaths or loves by hoping for it in the groundswell of a Sirkian moment. A Sirkian moment: if Sirk treats his characters as flat icons, images in a mirror, whose feelings are better expressed by the scene behind them, the lighting on them, than by themselves, Sirk’s best corollaries are the early Renaissance painters painting myths, Christian or Greek. Like any mythmaker, Sirk’s undertaking is simply to stage emotional connections as physical ones. Magnificent Obsession shows how preposterous the world would be if it conformed to our desires, and beautiful. The smallest events, as Rock Hudson romantically intones med school dialect on a beach, and starts surgery shirtless, have as little logic as the big ones, the stacked-up coincidences and revelations and the final miracle. As the central scenes looked imagined out of black, the whole thing plays as someone’s, Hudson’s, stream-of-consciousness imagination: the wish-fulfillment, the fear-fulfillment, the cartoon characters, single emotions personified and exposed, moved through the plot like game pieces.

Like Benjamin Button and Daisy, Magnificent Obsession’s characters are painted clay, bodily stand-ins for universal emotions, ciphers that give the audience an entry point to live their experiences. In Button, whatever the lovers great emotional attachment, they are, first and foremost for Fincher, bodies, and bodies that can only love each other once. That Benjamin ages backwards from an old man to a young child is much less the great surrealistic concept it could have been, with an octogenarian gorging himself with sugar and screaming when it’s taken away, than a means of making the audience realize what they know too well to see otherwise, that their thoughts and feelings are made possible only by their bodily experience in the world.

Which is why it’s weird that Fincher deliberately flattens his characters into computer animations—there’s never a sense that they exist in three-dimensions: they're in a painting. But Sirk, with his receding hallways, and windows, and doorframes, lets his characters step beyond the abstract patterns in the background, and beyond the flat mirrors: he gives them space to move, to exist in, a stage. Their movement is always perfectly blocked, emotional connections staged physically, their inner worlds reflected in the scene. Here, “surgery” is not just religious, but sexual, one body curing another.

A couple last examples.

Some windows.

Characters drawn like curtains, or an annunciation painting, on either side:

The whole world in a doctor’s hands:

Beauties at hand:

Distant beauties, as happiness recedes:

Hidden paradises, worthy of a salad dressing label:

And as Jane Wyman clings to a phallic symbol, Rock Hudson opens the world:

This isn’t how John Ford uses windows, to show worlds apart from the characters that they'd like to get at. Sirk uses windows as Renaissance painters used them, to open up a small room into an epic space of seas and stars, and place one loft’s drama as the central scene of the world. Magnificent Obsession’s final hospital of many is set in an abandoned desert valley, as if it’s the theater of Eden (Sirk claimed his own theme as the recovery of lost innocence). Background flowers and trees confirm the lovers’ intimations of paradise, and the blatant fact that all these sights are matte shots, painted on a wall, is just Sirk’s usual sincere/ironic double bind: to show the world as beautifully as possible, he’s got to show it artificially, and transparently so. That’s just expressionism. Sirk has no desire that anyone thinks they’re watching an objective portrait of two people in 1954. As the windows indicate, it’s a romance of the cosmos.

One more example.

As a narrative filmmaker Sirk isn’t always Sirk. Magnificent Obsession is padded out with insert shots of men getting in cars and cute patter and other scenes of transition and exposition that the Hollywood narrative needs to function. But Sirk is essentially an avant-garde filmmaker, until Imitation of Life more interested in light and shadow than the knots of character psychology, always as diagrammatically simple as a Freud proof, while light and shadow are relative, never fixed.

The culminating scene plays like Beethoven, one theme building and breaking and transmuting into another quite opposite one that builds again. It’s a scene, like most of Magnificent Obsession, of alternating hell and paradise, the one in which the lovers kiss and say they love each other more than is humanly possible, which is probably true; the one in which Hudson appears from thousands of miles away just because Wyman wants him to, in which everything is lit from dark (“it gets darker at night,” Wyman says blind), and Wyman slowly tracks around her apartment hands out-stretched, less sightless than a sleep-walker. It’s a dream sequence. Lost in the dark, Wyman still manages to grasp a phallic bedpost and get to the terrace to kill herself. But (first polar switch) a flower pot falls from the ledge, its crash shatters her trance, the operatic music cuts, and she hears a knocking at the door—as if it’s also woken her from the suicide mission. Come miraculously, Rock Hudson steps from behind a grate to greet her, just as she’s stepped from a window curtain to the ledge a moment before, both ready to confront their secret desires, just as when she rises from her bed Sirk’s camera pans up to see her as a beacon of light in black. In a pot-split second the film goes from nightmare to waking dream.

There’s nothing else but them and their desires. They kiss, and it’s literally their shining moment.

Their kiss is the moment that leads to Vertigo—as the waves’ crash is a victory over drowning in Hitchcock, the kiss here plays like salvation from death, and even as Hudson attacks Wyman like a vampire, he holds her from the shadows. The threat of death makes their love sublime, and the scene works only because it’s as absurd as what it’s showing: a playboy in love with a blind old lady he saw a couple times in a hospital and on a beach, and the old lady in love with him.

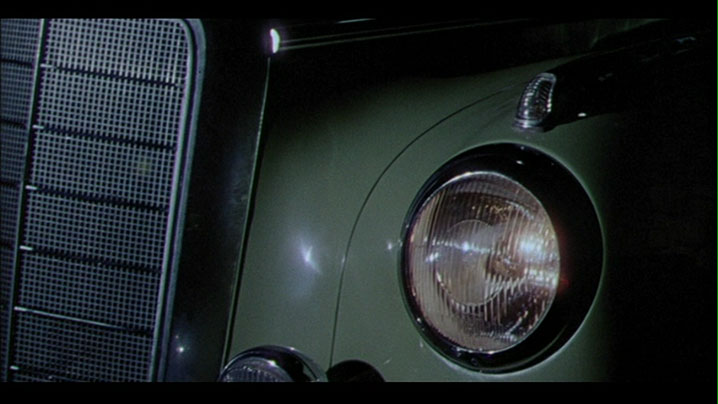

The music hushes, cuts, and the two take a midnight ride to the middle of nowhere in rural Switzerland. They talk of how perfect the moment is—just as they’d imagine it. Unaccountably, shadows flick across them in the car. But Sirk starts the scene with a pan-up from the car’s headlights—another ball of light, like Mrs. Phillip’s lamp and a recurring yellow umbrella—that plays sun in endless night.

Again starts music, a Swiss jig. They enter a town that looks, says Doherty, like the inside of a cuckoo clock. Sirk’s camera pans down to the dancers, then up to the straw witch they burn—the movie’s oblique political moment—again showing a flare of deathly light in their ongoing consummation (“fireworks bursting all over the place” says Hudson), as they again imagine a scene—dancing—and again it appears as if by invocation in a cross-fade as one dance changes into another and they waltz across the floor in some perfect Ophulsian restaurant where the waiters and musicians have to stay up all night for two people whose world always revolves around them. “This isn’t such a bad place after all,” says Wyman in a barroom paradise to match a barroom hell of whores from act I.

Another fade—the same song continues with slower, lusher orchestration as they kiss at the end of the hallway, then step out of the shadows, and Hudson leads her back in the film’s single shot that doesn’t stand apart to frame them, but tracks behind them, and joins them. Will they or won’t they? It’s a play of light and shadow.