Many critics accuse directors like Terrence Malick, Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne, and Asghar Farhadi of making the same movie each time out. The inherent laziness of this argument says more about the writer than the artist, but it also easily disregards stylistic and thematic motifs that are still evolving within a body of work. Japanese master Hirokazu Kore-eda regularly experiences such reductive forms of analysis. Quietly patient and wise, his films are breezy dramatic miniatures that examine the nuances of everyday life. Most impressively, they challenge preconceptions about dramatic redemption, giving conflicted characters the opportunity to grieve, learn, rejoice, and evolve at their own pace.

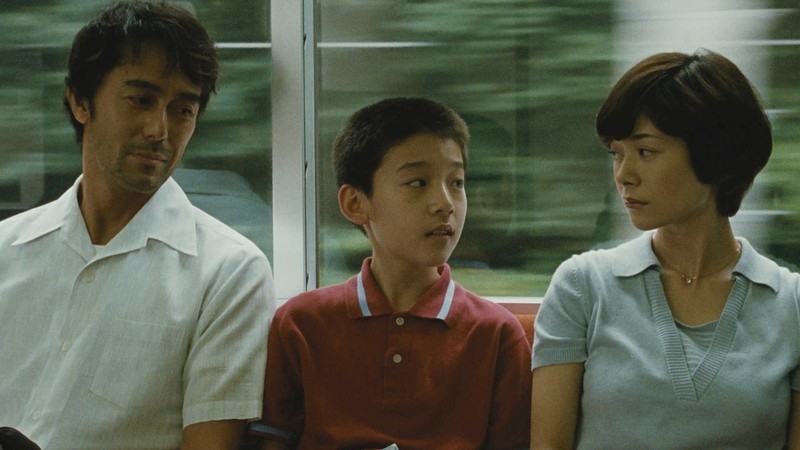

Kore-eda’s After the Storm follows a similarly measured trajectory. It appreciates the present moment even as its lead protagonist continues to dwell on the past. Once a successful novelist, Ryota (Hiroshi Abe) moonlights as a private detective using the job’s free-ranging latitude to spy on his ex-wife Kyoko (Yōko Maki) and young son Shingo (Taiyô Yoshizawa). The failed marriage has only emboldened his destructive gambling addiction, foreshadowing a downward spiral fueled by paralyzing self-pity.

Ryota’s recently widowed mother Yoshiko (Kirin Kiki) works as the lynchpin between generations. Newly liberated from four decades of marriage, she suddenly sees hope and possibility where only routine once existed. Kore-eda contrasts her vibrancy with the middle-aged apathy of Ryota and Kyoko, and the youthful curiosity of Shingo. In the film’s moody first half these characters spend ample amounts of time orbiting each other, momentarily colliding before going on their separate ways. Casual conversations hide deeper feelings of unchecked guilt and regret left to fester underneath the surface.

This changes when all four characters are sequestered in Yoshiko’s cramped apartment after getting besieged by a massive typhoon. The closed quarters and prolonged duration help destroy the alternate reality that Ryota has constructed around his personal failures. No longer a sleuth, or a writer, or a con man, he’s finally forced to be a father. Here, After the Storm condenses the intricate human concerns of the director’s recent work, most notably Our Little Sister (2015) and Like Father, Like Son (2013).

Visually, Kore-eda sees the family living room much like John Ford views Monument Valley—as a vast landscape of colors, objects, and details that emotionally deepen characters within the frame. Yoshiko’s small domicile is packed with old pictures, antiques, and trinkets that help recalibrate her family’s appreciation for the here and now. But Ryota struggles mightily while experiencing the gradations of change, proving that the process is nuanced and ongoing.

The film occasionally suffers from an overabundance of witticisms, with lines of dialogue feeling like gloomy Hallmark cards. At one point, Ryota tells his son, “Listen, it’s not that easy growing up to be the man you want to be.” More than usual, Kore-eda relies on dialogue as a crutch to express obvious themes. But the performances organically connect to the torment expressed in these words, avoiding what could have been pitfalls into sentimentality.

Melancholy looms over After the Storm even after it reaches a somewhat sunny conclusion. Kore-eda wants the sting of regret to linger, not as an all-encompassing force but a subtle reminder of the past. Thematic dualities of this kind populate much of the film: easy money vs. hard work; absence vs. presence; denial vs. acceptance. Like his own father, Ryota struggles to break free of his acting on bad habits. Both men have embraced juvenile chaos and wish fulfillments, making a life of consequence and responsibility feel almost pedestrian.

After the Storm brilliantly deconstructs this self-destructive cycle over time. It patiently strips away male delusions of grandeur and focuses intensely on the responsibility of being mindful. “I wonder why it is men can’t love the present,” Yoskiko rhetorically asks late in the film. With this comment she essentially becomes a proxy for Kore-eda himself, who has spent his entire career reminding audiences to live in the moment. It’s a poignant lesson that bears repeating over and over again.